Prisons

Doorways to a dark past.

First established by French colonists in 1862, Con Son prison was taken over by the Americans and transferred to the South Vietnamese government in March 1955. Captives were political dissidents, communists and Viet Cong, but also any citizen that the government wanted to break and make disappear: writers, student protestors, Buddhists, people who refused to salute the flag. The prisons were finally closed in 1975, ending a horrifying chapter in history where more than 20,000 people died.

Phu Tuong Prison (Trai Phu Tuong) is one of the most prominent sites. On Nguyen Van Cu Street just east of the museum, it was built by the French in 1940 and continued to be used by the American-backed South Vietnamese government. There are 120 chambers with an additional 60 without a roof. Skeletal mannequins in several of the cages add a bone chilling realism to the experience.

A cell at Phu Tuong.

If the prison was considered hell on earth, then the “tiger cages” were the deepest, darkest part of it.

In 1970, Tom Harkin, an ex-Navy pilot and amateur photographer working as an aide to a congressional delegation, convinced two Congressmen to investigate the rumour of tiger cage-like cells on Con Son. Accompanied by interpreter Don Luce, on the scheduled inspection of the prison they diverted from the planned tour and found the nondescript door using a map drawn by a former prisoner. They demanded entry. What they saw was horrific.

Fettered prisoners were kept like animals in concrete pits, with the bars on the ceiling above. There were three to five prisoners in each cage, 400 to 500 in all, and at least half were women; one girl was only 15 years old. They were diseased, starving, bloodied, filthy, doused in skin burning quick lime and near death. Read a brief account of what Don Luce saw.

Grim.

Despite resistance Tom Harkin took photos that would later be published in the July 17, 1970 issue of Life Magazine, exposing this crime against humanity to the world.

Phu Tuong Prison is open from 07:30-11:30 and 13:30-16:30. If there’s someone at the booth, pay a small admission fee which will give you access to all the prisons. After you enter the main door, head right. Ensure you are out of the prison well before lunch and closing time – we learned firsthand that you do not want to get locked in.

The tiger cages will leave an indelible impression.

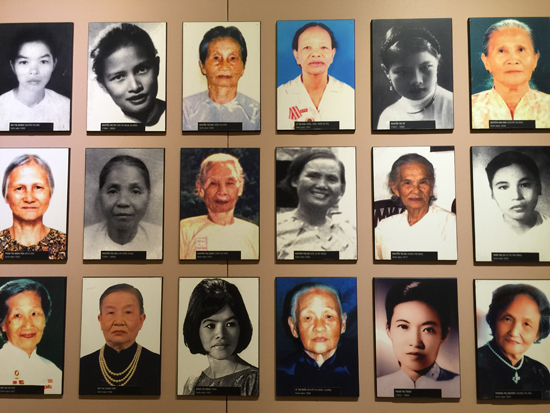

Adjacent to Phu Tuong is Trai Phu Phong, known as Camp 5 and used from 1962 till 1973. First used for military criminals and POWs, it later became the jail for women. Women and children were not spared from torture or death, and in 1969, some women disembowelled themselves en masse in front of prison wardens as protest. At the time of liberation in 1975, Con Dao had 494 female prisoners. You can read the story of Thieu Thi Tao who was arrested at the age of 18 and spent seven years in Con Son – she was being held in the tiger cages when Harkin, Luce and the US congressmen uncovered them.

Con Dao’s female prisoners.

Located in the centre of town (on Le Van Viet Street behind Saigon Con Dao Resort), this prison has had many names including Bagne I, No.1 Prison, Cong Hoa, No.2 Prison and now finally Phu Hai Prison (Trai Phu Hai). Originally built in 1862, it was the first and the biggest prison of Con Dao. It was 12,015 square metres, with 10 big lockups, 20 rooms for solitary confinement (where prisoners were kept in darkness around the clock) and a special jail for prisoners facing the death penalty. It detained a variety of prisoners. There was also an area for breaking stone and a cellar for rice husking, a punishment that was known as “a prison in prison, a hell in hell”. Six shackled prisoners pushed the grinding mill around and around in a hot cellar full of suffocating, lung filling dust. Like Trai Phu Tuong, this site has opening hours 07:30-11:30 and 13:30-16:30.

Some lesser known prisons are found on the eastern edge of town, on a street running north off of ocean road Nguyen Van Cu, across from Lo Voi Beach (there’s a blue sign). Gates are unlocked, you are free to visit at leisure and you will not likely see any other visitors. Built in 1968, Phu An Camp (called Camp 6 until 1973) was part of the new jail system designed by the Americans. It had two rows of 10 chambers and four cells, and incarcerated those arrested in the Tet Offensive.

Directly across the road is Phu Binh Camp or Camp 7. Built in 1973, it contains American-style tiger cages. When President Duong Van Minh and the South Vietnam government surrendered on April 30, 1975, officials in Con Dao locked all the prison doors and fled. At 01:00 on May 1, 1975, Camp 7 was the first prison to begin an uprising that spread across the island. By 08:30 Con Dao was completely liberated.

Trai Phu Binh (Camp 7).

Other sites

In 1873, the town’s central pier known as Quay 914 began construction using prison labour. Over a span of several decades, 914 lost their lives in the construction.

On Vo Thi Sau Street leading north out of town, in the direction of the Con Dao National Park office, theCow Shed was built by the French in 1930. With a total area of 4,110 square metres, it had 35 chambers separated into three sections including Section C with 24 boxes, where prisoners were fed like pigs. The gate was locked when we visited.

In the shadows of the past, finding peace and light on Con Son.

Across the road from the Cow Shed is a memorial shrine for a mass grave that became the first cemetery of Con Dao prison. The plaque somewhat confusingly explains that a prisoner uprising on 28 June 1862 lead to a manhunt that resulted in 100 dead and 20 captured. At this site the 20 prisoners were forced to dig a mass grave for the dead, and then they were buried alive.

On the road through the national park to Ong Dung Beach are the remnants of the Ma Thien Lanh Bridge, also a French colonial construction that used prison labour. By the time the project was abandoned in August 1945, 356 prisoners had lost their lives. In the park you can also hike to So Ray, a plantation they were forced to work on.

Aftergrowth at So Ray Plantation.

Some 650 metres east of the museum on Nguyen Van Cu Street (the ocean road) is a plaque for the Hang Keo Cemetery, which was discovered in 1997. Used from the time of French colonialism to the 1940s, 10,000 prisoners were buried here over an area of 80,000 square metres. Found remains have been relocated to Hang Duong Cemetery, where visitors pay their respects nightly to revolutionary martyr Vo Thi Sau and all others who suffered and died on Con Son.

Newer articles

Older articles